- This week, as MetroConnects continues to celebrate Black History Month, we remember Fountain Inn’s Clayton “Peg Leg” Bates.

- “Peg Leg” Bates broke racial and disability barriers as he danced his way around the world, beginning in 1915.

An Accident That Secured a Destiny

Clayton “Peg Leg” Bates just might be the most famous of Greenville’s early 20th century mill workers, rivaled perhaps only by Shoeless Joe Jackson. And this, despite the fact that he only worked in Woodside Cotton Mill for two days before he lost his leg in a terrible accident. To him, though, the accident was not so terrible after all. “I thank God I lost this leg,” he is reported to have once said. “This might sound strange for you to hear me say, so I think I’d better explain why I feel this way. This leg brought me fortune and fame. As a matter of fact, that’s how I got my name. With this peg I do not have to beg, so I thank God I lost this leg.”

Bates was born in 1906 or 1907 in Fountain Inn. His father, Rufus Bates, was a laborer, and his mother, Emma Steward Bates, was a sharecropper and housecleaner. His parents divorced when he was four, and his mother had to work long, difficult hours to make ends meet. Bates worked in the cotton fields and also danced at barber shops for loose change — something his mother unsuccessfully tried to get him to stop doing, thinking that the men were laughing at her son. But Bates could not stop dancing and he kept going back for more!

When he was 11 or 12, Bates begged his mother to let him work at the Woodside Cotton Mill rather than continue the backbreaking work of picking cotton. He was technically too young for the job and she resisted at first, but his perseverance won in the end, fating him for the accident that was to come. Or was it destiny? Bates’s job was to climb on top of a pile of cottonseed and push it into a conveyor. On his second day, he climbed up and “caved in this pile of seed and slid down with it,” he said in a documentary about his life called The Dancing Man. His leg and two fingers on his right hand were crushed. Since most local hospitals would not accept Black patients in 1918, he was forced to undergo the amputation of his leg on his mother’s kitchen table.

A Star is Born

Fortunately, Bates recovered quickly and he was determined not to let his newly acquired “peg leg” — a wooden prosthetic made by his uncle — slow him down. He quickly learned to walk, then run, then jump on that leg. In less than two years, he was dancing again. He joined some traveling carnivals and minstrel shows, none of which seemed to make a go of it for too long. By 15, he was traveling the Vaudeville circuit.

He landed in Harlem during the height of the Harlem Renaissance when he got his big break: Leslie Lew, producer of the famous “Blackbirds” musical revue, spotted him performing and was impressed by his distinctive style, which included acrobatics, graceful soft shoe and powerful rhythm-tapping that made the most of the deep, bass tone given off by his prosthetic in combination with the metallic tapping of his other foot. Lew hired him to perform on Broadway’s Blackbirds of 1928, which also featured performers like Bill “Bojangles” Robinson during its historic 528 show run at the Liberty Theatre, becoming the longest-running all-Black show on Broadway.

A Performer Fit for Kings

Bates went on to travel the world, including Paris, where he performed at the famous Moulin Rouge, and England, where he was invited twice to perform for the King and Queen.

Despite his success, he continued to be met with racism in the United States. When he performed in Washington D.C., for example, he had to perform in Black face so that audience members would think he was white. Once again, though, he was undeterred by the struggles he faced. He went on to headline the Cotton Club and Apollo Theater in Harlem. He performed with some of the most important jazz orchestras of the time, including Count Basie, Erskine Hawkins, and Duke Ellington orchestras.

His acrobatic style even caught the eye of Ed Sullivan, and he appeared on the Ed Sullivan show more than 22 times. Here, he would fly through the air, landing on his peg and continuing to bounce to the rhythm of the orchestra. It was painful, people close to him recalled in the documentary, with one person saying that there were times that he would sit in the dressing room and cry from the pain. But that never stopped his dancing.

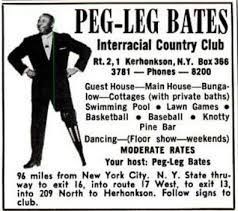

Peg-Leg Bates’s Interracial Country Club

Nor did his struggles stop him from contributing to the Black community. Frustrated by segregation laws that barred Black people from entry into some of the resorts where he performed, he decided to open a resort and club that would welcome all. In 1951, he and his wife opened the Peg Leg Bates Interracial Country Club in Kerhonkson, New York, and operated it for nearly 40 years.

Bates continued to dance well into the 1980s, and early 1990s. He continued to appear at speaking engagements as he neared his 90s. He was 91 years old when he passed away on December 8, 1998, just one day after he was awarded the prestigious Order of the Palmetto award in Greenville. Today, a statue and historical marker stands in his honor on North Main Street in the courtyard of Fountain Inn’s City Hall.

Keep up with all of MetroConnects’ Black History Month Spotlights at www.metroconnects.org/recent-news/.