MLK’s Commitment to Black Workers’ Rights

January 15, 2024, marked the 95th birthday of legendary Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. King’s impact on the United States and the world has been, of course, extraordinary — from his pivotal role in forever changing entrenched systems of segregation in the U.S., to spearheading the Civil Rights Act of 1964, his legacy continues to shape everyday life in America today. At MetroConnects, King’s legacy is particularly poignant, as he was fighting for the rights of sanitation workers like our very own when he was assassinated on April 4, 1968.

For Dignity and Rights

On April 3, 1968, King was in Memphis, Tenn., where he delivered his now famous speech, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop.” He was there in support of the Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike, saying in his speech “The issue is injustice. The issue is the refusal of Memphis to be fair and honest in its dealings with its public servants, who happen to be sanitation workers.” King’s participation in the strike was part of a larger commitment to his national Poor People’s Campaign, which demanded jobs, unemployment insurance, a fair minimum wage, and education for poor adults and children. The Poor People’s Campaign was seen as the next step toward equality after the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 went into effect — a way of combining the legislative acts with economic security and dignified employment for Black people and other marginalized populations. The Sanitation Workers Strike was about just that — equality, economic security, and dignity.

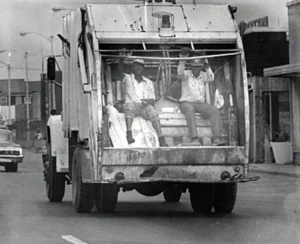

The strike began on February 12, 1968, when 930 of 1,100 sanitation workers did not show up for work, including 214 of 230 sewer drainage workers. While Memphis sanitary workers had long been struggling with low pay, long hours, and dangerous working conditions, the breaking point came with the deaths of Echol Cole and Robert Walker, two garbage workers who were killed when they sought refuge from the pouring rain in the compactor area of the garbage truck. They had earlier been prevented from seeking shelter inside a nearby building due to segregation laws. When they stood under the compactor out of the rain, the compactor shorted and began to close. A malfunction prevented the driver from stopping the compactor and keeping it from crushing the two men.

Following their deaths, their widows received no insurance benefits. The city offered only one month’s pay for each man, and Walker’s wife (who was pregnant with their sixth child at the time) was offered an additional $500 for funeral expenses “if you need it,” according to a letter from the city. This injustice brought home the indignities that workers were forced to endure: Wages so low that many had to rely on welfare and public housing; the back-breaking and dirty work of carrying heavy, open tubs of seeping garbage; and the lack of city-issued uniforms. White colleagues — who usually had the less treacherous job of driving the trucks — were offered shower facilities and places to change clothes before they returned home for the day, but because of segregation laws, Black workers were refused this benefit. Many workers admitted that their families asked them to remove their clothes at their doorways when they arrived home, due to the smell and the filth.

MLK’s Impact

Months into the strike, Mayor Henry Loeb was still unmoved by the workers’ demands. Before becoming mayor, Loeb had been head of the city’s sanitation department, where he enforced the very working conditions that were being protested (learn more from the “Southern Hollows” podcast below). In a speech on March 18, more than a month into the strike, King praised the workers, saying, “Whenever you are engaged in work that serves humanity and is for the building of humanity, it has dignity, and it has worth” (History.com).

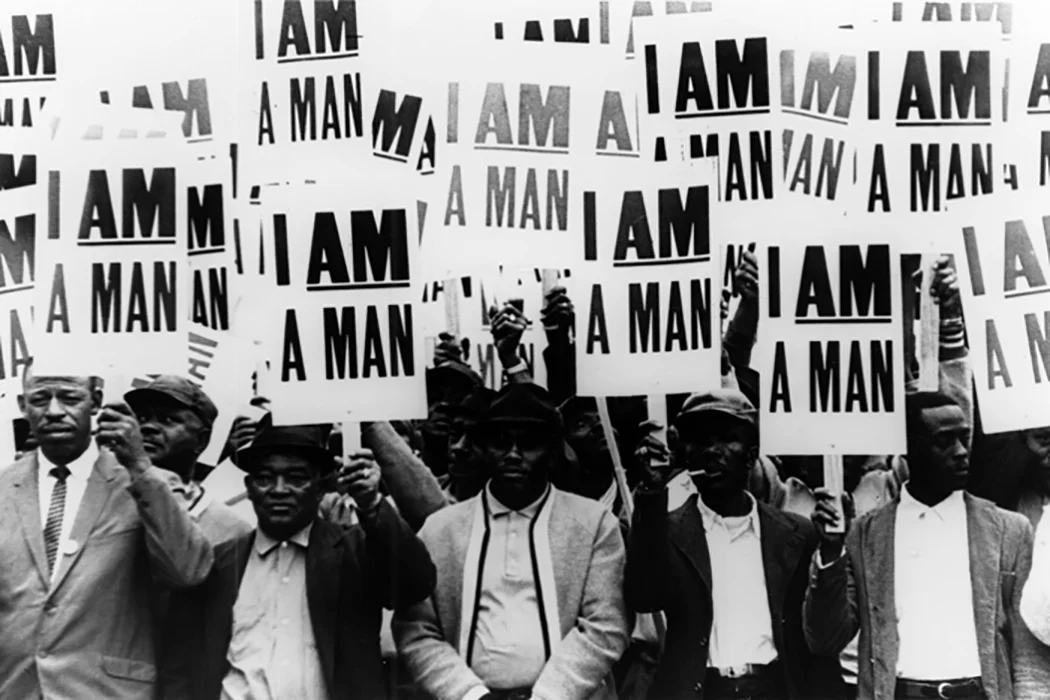

On March 28, King returned to Memphis to lead another march. Unfortunately, the crowd of more than 22,000 people became difficult to manage. King called off the march, but not before a police officer shot and killed a Black teenager who was participating. Despite the tragedy, the workers were not deterred. They continued to strike and to march, wearing sandwich boards that declared ‘I am a Man,” demanding their dignity be recognized. When King returned to Memphis on April 3, he reiterated the call for dignity, reminding the crowd that “there is no stopping point short of victory.” King was shot and killed on the balcony of the Lorraine Hotel the very next day.

It was bittersweet, then, when the City of Memphis, at the urging of President Lynden B. Johnson, reluctantly agreed to grant the workers raises and recognize their rights to unionize two weeks later. Despite the win, the struggle for equal treatment continued for many years in Memphis and elsewhere in the country, with King’s final words still ringing in the air: “Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land.”